Menu

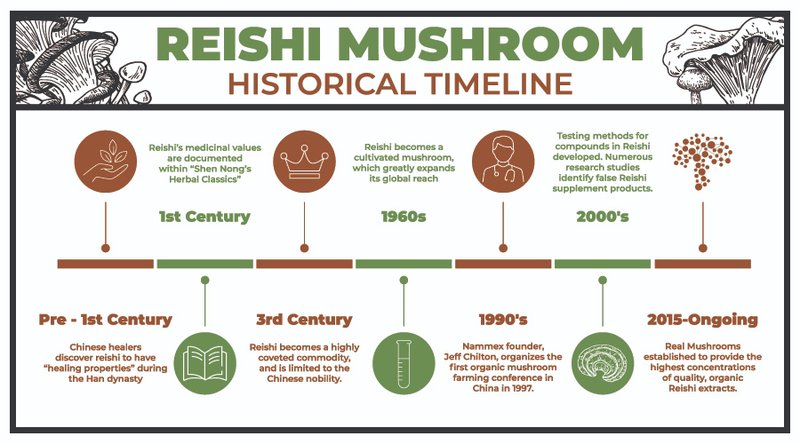

Documented references to reishi’s reputation as a human health booster date back as far as 2,400 years, and depictions of it frequently appear in ancient Chinese and Japanese artwork. However, the mushroom (fruiting body) has likely been in use as a functional herb for over 4,000 years across the Eastern hemisphere, including both Korean and Indian cultures [1]. Read on to learn about reishi mushroom history and why it came to be so revered in Asian culture.

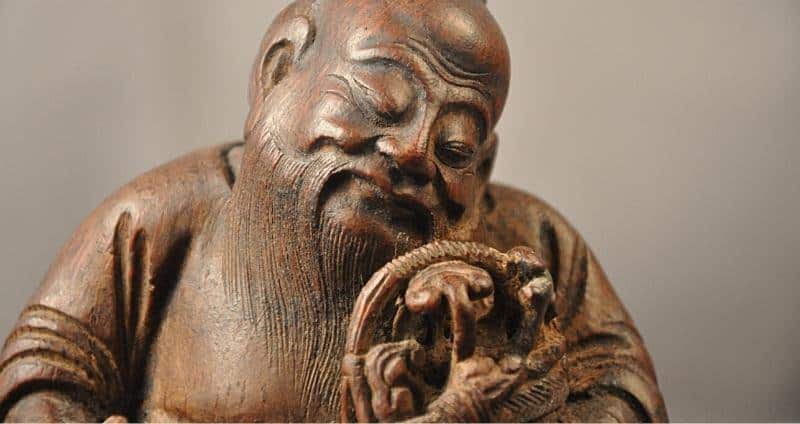

Ancient Chinese herbalists called reishi Lingzhi (灵芝) because it means “herb of spiritual potency.” Emperor Yan, the first (and most legendary) in the line of ancient China’s rulers, is the founding father of the farming practices and tools that became the foundation of China’s agriculture. He is also the attributed author of the “bible” of medicinal plants: Shennong Ben Cao Jing (a.k.a. Materia Medica). Of reishi, he wrote, “If eaten customarily, it makes your body light and young, lengthens your life, and turns you into one like the immortal who never dies.”

Traditional Chinese Medicine physicians adopted the phrase “the mushroom of immortality” to describe the all-encompassing health support that they deemed reishi could provide [2]. Reishi was revered for its health-promoting effects and medicinal properties in ancient China, yet it was relatively rare in nature, so for a long time, it was reserved exclusively for nobility.

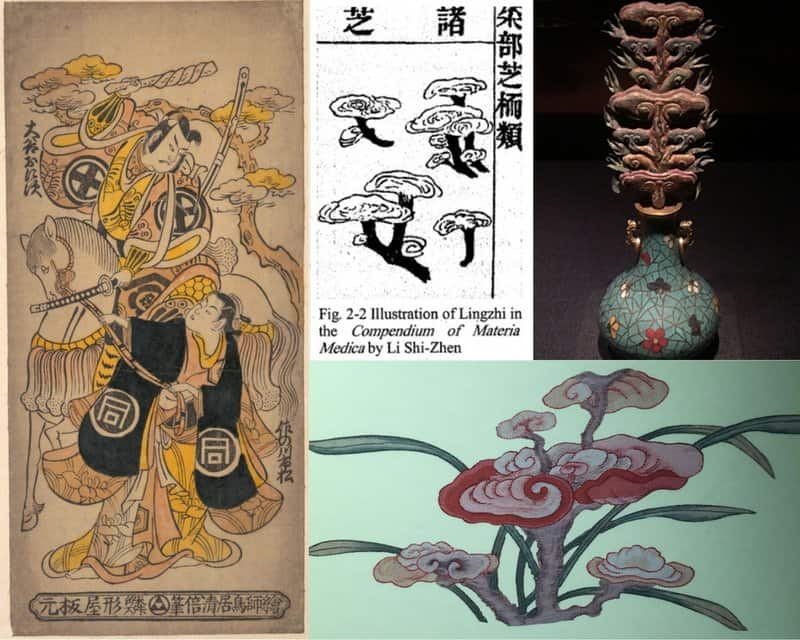

Since reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) was and still is considered one of the most prized medicinal herbs in Chinese medicine, it has often been depicted alongside other powerful symbols in art. For example, in a 16th-century silk painting by Qiu Yang, reishi is presented as a gift to the most worshipped goddess in Chinese mythology, the Queen Mother of the West. Another example is the wall painting ChaoYuanTu from the Ming dynasty. In it, there are maids holding reishi as gifts to the emperors.

Many Chinese folk tales, myths, and poems also feature reishi. For example, the myth of Magu tells of a beautiful folk woman who lived on Guyu Mountain and practiced Taoism. Magu used the water from the 13 springs on the mountain to brew reishi wine. After 13 years, the wine matured, and Magu became immortal [5]. Magu features in both Chinese and Korean literature. She is typically portrayed as having healing powers and as having gifted the world with the healing herbs of cannabis and reishi.

Cultural reishi mushroom history is filled with the wonder this unique mushroom evoked in people. Thematically, reishi consistently appeared as a transformative, healing, and even divine medicinal herb for its health benefits.

Ancient Chinese texts discuss the six colors of reishi with the most common and well-known being the red variety; other colors include blue, yellow, black, white, and purple.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners prescribe Lingzhi to influence the heart, lungs, liver, and kidney channels, balance Qi (the body’s life force), calm the mind and relieve cough and asthma.

As we discuss in our article, The Benefits of Red Reishi and the 5 Other Color Types, mushroom expert Zhi-Bin Lin notes that modern pharmacological studies show reishi’s potential for supporting cardiovascular health. He goes on to suggest that these benefits could possibly relate to the “heart-boosting” effects recorded in Traditional Chinese Medicine texts [3].

Reishi mushrooms are included in China’s State Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (2000) and are touted to balance Qi, ease the mind, and support respiratory health [4].

Reishi remains a cornerstone of natural medicine in Eastern cultures. With globalization and the growing number of people looking for natural solutions to support their health, scientists are now investigating the validity of the health claims surrounding this traditional herbal remedy.

Read one of our other articles about reishi mushroom to learn about its incredibly diverse applications for health and wellness:

1. Wasser, Solomon P., 2005. Reishi or Ling Zhi (Ganoderma lucidum). Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. DOI: 10.1081/E-EDS-120022119. 16. Kanmatsuse, K., Kajiwara, N., Hayashi, K., Shimogaichi, S., Fukinbara, I., Ishikawa, H., & Tamura, T. (1985). Yakugaku zasshi : Journal of the Pharmaceutical Society of Japan, 105(10), 942–947. https://doi.org/10.1248/yakushi1947.105.10_942

2. Loyd, A. L. et al. (2018) ‘Identifying the “mushroom of immortality”: assessing the ganoderma species composition in commercial reishi products’, Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, p. 1557. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01557.

3. Wachtel-Galor S, Yuen J, Buswell JA, et al. 2011. Ganoderma lucidum (Lingzhi or Reishi): A medicinal mushroom. In: Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, editors. Herbal medicine: Biomolecular and clinical aspects. 2nd edition. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; Chapter 9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92757/

4. Lin, Z. (2009). Lingzhi: From mystery to science.

5. Du, Q., Cao, Y., Liu, C. (2021). Lingzhi, An Overview. In: Liu, C. (eds) The Lingzhi Mushroom Genome. Compendium of Plant Genomes. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75710-6_1

Disclaimer: The information or products mentioned in this article are provided as information resources only, and are not to be used or relied on to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. This information does not create any patient-doctor relationship, and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment. The information is intended for health care professionals only. The statements made in this article have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Any products mentioned are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The information in this article is intended for educational purposes. The information is not intended to replace medical advice offered by licensed medical physicians. Please consult your doctor or health practitioner for any medical advice.